Black authors are still underrepresented in UK publishing

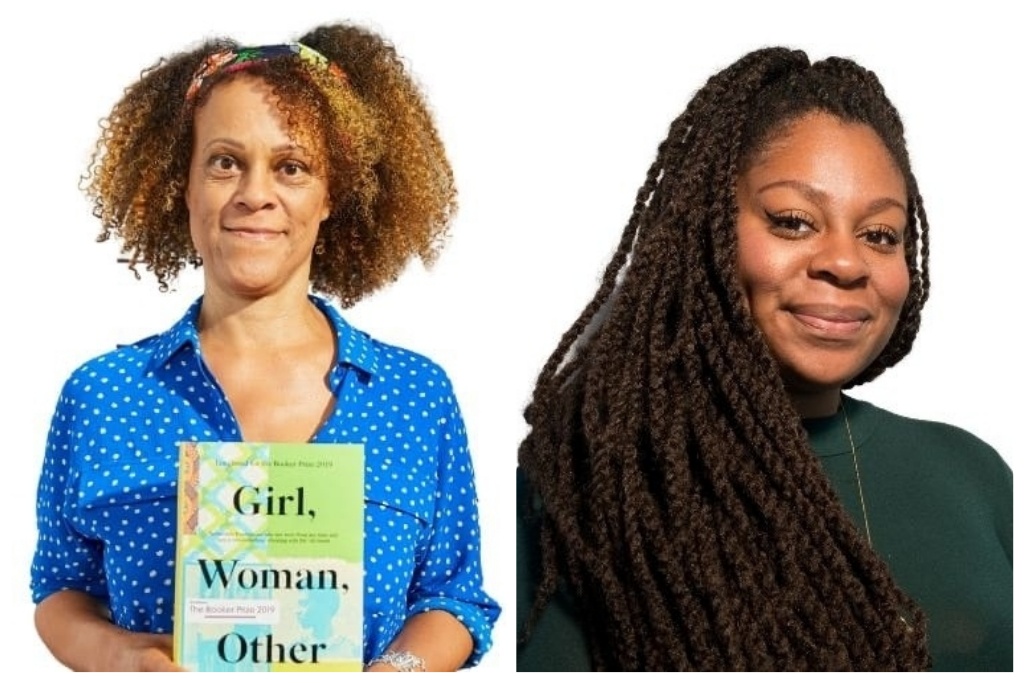

As people seek to educate themselves in response to Black Lives Matter protests, sales of books by black British authors, such as Reni Eddo-Lodge and Bernadine Evaristo, have topped the UK bestseller lists. Several recent prestigious awards have also been won by black writers, including Candice Carty-Williams who won book of the year for Queenie at the British Book Awards. Although proud of her achievement, she was also “sad and confused” on discovering she was the first black author to win this award in its 25-year history.

While these firsts must be celebrated, they also shine a light on publishing’s systemic practices, which have maintained inequalities and under-representation for black, Asian and minority ethnic writers and diverse books. Despite awareness of its shortcomings and years of debates and initiatives (diversity schemes, blind recruiting practices and manuscript submission processes) the industry has generally failed to achieve lasting change.

A growing body of research in this area has found that this is because they fail to address wider inequalities faced by people of colour, which compounds the lack of representation in the industry.

A substantial market

Our own research on diversity in children’s publishing began with a review of the existing literature. We then conducted an online survey, which received 330 responses and 28 in-depth follow-up interviews with people working across the sector.

The results provide further evidence on a number of issues, with our participants from across the sector confirming that a key barrier has been the ingrained perception among industry decision-makers that there is a limited market for diverse books. This is a belief that books written by black and diverse authors or featuring non-white characters just don’t sell.

This perception is seen across the industry, including in children’s literature. This is despite evidence of substantial markets. For instance, a third of English primary pupils are from a black, Asian or minority ethnic background. However, a report by the Centre For Literacy in Primary Education revealed that although the number of black, Asian and minority ethnic protagonists in children’s books had increased from 1% in 2017 to 4% in 2018, there is still a long way to go to achieve representation that reflects the UK population.

Similarly, Melanie Ramdarshan Bold’s research for the BookTrust reported that only 6% of children’s authors published in the UK in 2017 were from ethnic minority backgrounds, only a minor improvement from 4% in 2007.

Our participants reported that a lack of role models meant that children and young people of colour were less likely to aspire to careers in the sector. This was compounded by the lack of diversity, particularly in senior roles, in publishing. For those who had pursued a publishing career, experiences of everyday racism and microaggressions were widespread. This added to feelings of frustration and a sense that they were not welcome or did not belong in the industry.

Commissioning problems

This all has a knock-on effect on what gets published. Authors of colour that we spoke to expressed frustration about the commissioning process. This included quotas for books by or featuring people of colour, a perceived limited appeal for these books and a feeling that authors of colour could only write about race issues.

Reliance on “traditional routes” to publishing also disadvantages black and working-class authors. Publishers reported receiving high volumes of submissions and heavy workloads, which meant they relied on established writers rather than seeking out new, diverse talent. This has the impact of narrowing the pool of authors from which books are published.

Our participants – including authors, illustrators, editorial assistants and agents – widely reported that a lack of cultural understanding also led to the view that diverse books are a riskier investment. They explained how limited promotion and marketing budgets often resulted in lower sales, reinforcing perceptions of limited demand. From their experience, miscommunication at subsequent points along the supply chain about the demand for and availability of diverse books means that those that are published may not even reach bookshop shelves.

These interconnected factors (among others) contribute to what Ramdarshan Bold described as a negative cycle, which perpetuates the lack of representation of minorities across all parts of the sector. This includes the lack of authors of colour being nominated for prizes and awards. Recommendations from our research include ensuring diversity on selection panels for events and awards and some good work is already taking place. However, more systematic collaboration and commitment from the sector will be required to produce lasting and meaningful changes and achieve equality and representation.

Our research participants pointed out that social media was allowing individuals to more effectively come together and raise their voices in support of diversity and representation. They expressed hope that this may help to drive forward meaningful and lasting change in the sector. There are signs that this may be the case with recent campaigns emerging in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The #publishingpaidme campaign highlighted racial disparities in publishing advances. The publisher Amistad, an imprint of Harper Collins dedicated to multicultural voices, ran the campaign #BlackoutBestsellerList and #BlackPublishingPower to draw attention to black authors and book professionals and demonstrate the market for these books.

The newly formed Black Writers’ Guild, including many of Britain’s best-known authors and poets, wrote an open letter airing concerns and demanding immediate action from publishers. The hope is that these campaigns can focus the industry on bringing about meaningful change.

This article was amended on August 21 to clarify that the project was informed by previous research, featured in the authors’ literature review.![]()

Catherine Harris, Research Associate, Sheffield Hallam University and Bernadette Stiell, Senior research fellow in the Sheffield Institute of Education, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.